Marvel Studios Is Dealing With A Decades-Long Comics Problem

Like any good superhero, Marvel Television has returned from the dead. The label is what the Marvel Netflix shows like "Daredevil" and the ABC ones like "Agents of S.H.I.E.L.D." were made under. Marvel Television was rendered defunct in 2019 after Marvel Studios absorbed it. Now, though its operations remain under the studio's purview, its name is being used again as part of an effort to more cleanly delineate the projects of the Marvel Cinematic Universe.

Marvel Studios will continue to be the label of the films, while Marvel Television will headline upcoming Disney+ programs like "Agatha All Along" and "Daredevil: Born Again." Marvel Animation will cover projects like the excellent "X-Men '97" (which is not part of the MCU), while Marvel Spotlight is for small-scale projects like "Echo" (read our review here).

Brad Winderbaum, Marvel Studios Head of TV, Streaming, and Animation, explained in an interview with ComicBook.com that, "We want to make sure that Marvel stays an open door for people to come in and explore." He continued:

"Part of the rebranding of Marvel Studios, Marvel Television, Marvel Animation, even Marvel Spotlight is to, I think, try to tell the audience, 'You can jump in anywhere. They're interconnected but they're not. You don't have to watch A to enjoy B. You can follow your bliss. You can follow your own preferences and find the thing you want within the tapestry of Marvel."

Marvel Studios really should've seen this issue coming because it's the problem that Marvel Comics has long been dealing with. How does a story hook new fans when the entry-level appears too high?

Untangling the Marvel Cinematic Universe web

The MCU has been criticized for lack of direction post "Avengers: Endgame," the movie that paid off the much-hyped clash between the MCU's heroes and Thanos. One reason? The MCU got too big. When Disney+ first launched, Marvel Studios tried to make the new TV shows an active part of the narrative previously confined to the films.

"WandaVision" set up Scarlet Witch (Elizabeth Olsen) as the villain of "Doctor Strange in the Multiverse of Madness." "The Falcon and the Winter Soldier" was a chapter in Sam Wilson's (Anthony Mackie) journey to become Captain America in time for the fourth Cap movie, "Brave New World." "Loki" introduced Jonathan Majors as Kang, who was (emphasis was) going to take over Thanos' big bad role.

Spinning such a tangled web meant following the MCU felt less like entertainment, and more like homework. This is an even worse problem with Marvel (and DC) comics, which have been published for decades in much higher volume (one 20-30 page issue a month) than the movies and TV shows are.

The interconnectivity adds to the paralysis of too much choice. Every year, Marvel will publish huge "crossover" events, which drag in all the major titles, disrupting their own stories. Marvel Comics knows that their readers won't electively choose to buy every book they publish, so the crossovers are meant to instill an obligation that they do. In practice, as the MCU is discovering, it can just as easily alienate audiences who aren't already drinking the Kool-Aid or even make the faithful fall out of love.

Why Marvel Comics are so complicated

Winderbaum told ComicBook.com that the new Marvel divisions are meant to act like a smorgasbord for viewers the way the comics are. "[Marvel comics are] designed to just pop in, find something that you like, and use that to enter you into the universe, and then you can explore and weave around based on your own preferences," he said.

And yes, in theory, that's how the comics should operate. It does for me, but I'm not exactly a test case for general audiences. I'm someone who read dozens of Marvel encyclopedias in his youth and has countless pieces of fluff trivia memorized. I'm also a movie buff who has experience deciphering which artists I want to follow from work to new work, so mapping that experience onto comics (where there's a revolving door of writers and artists who go from series to series) is easy.

For someone who's never read an issue of "Amazing Spider-Man" in their life, though? That's more daunting. There's not only a lot of history, there's a lot of different comics being published, some under the same banner. Say you walk into a comic shop eager to read some "X-Men" after loving "X-Men '97." Do you pick "X-Men," "Immortal X-Men," "X-Men: Red," or something else? I can tell you what to do, but you shouldn't need me to.

Another example, I'm currently reading Matt Fraction and Salvador Larroca's "Invincible Iron Man" (published 2008 to 2012) for the first time. In the first arc, Tony Stark is the director of S.H.I.E.L.D. By the second, he's now a wanted fugitive and has been replaced in his Natsec role by Norman Osborn (yes, Green Goblin Norman Osborn). I know how this happened because I'd previously read "Secret Invasion," which explains it. But for an unversed reader? It'd be a big jump.

Too many crossovers for Marvel's own good

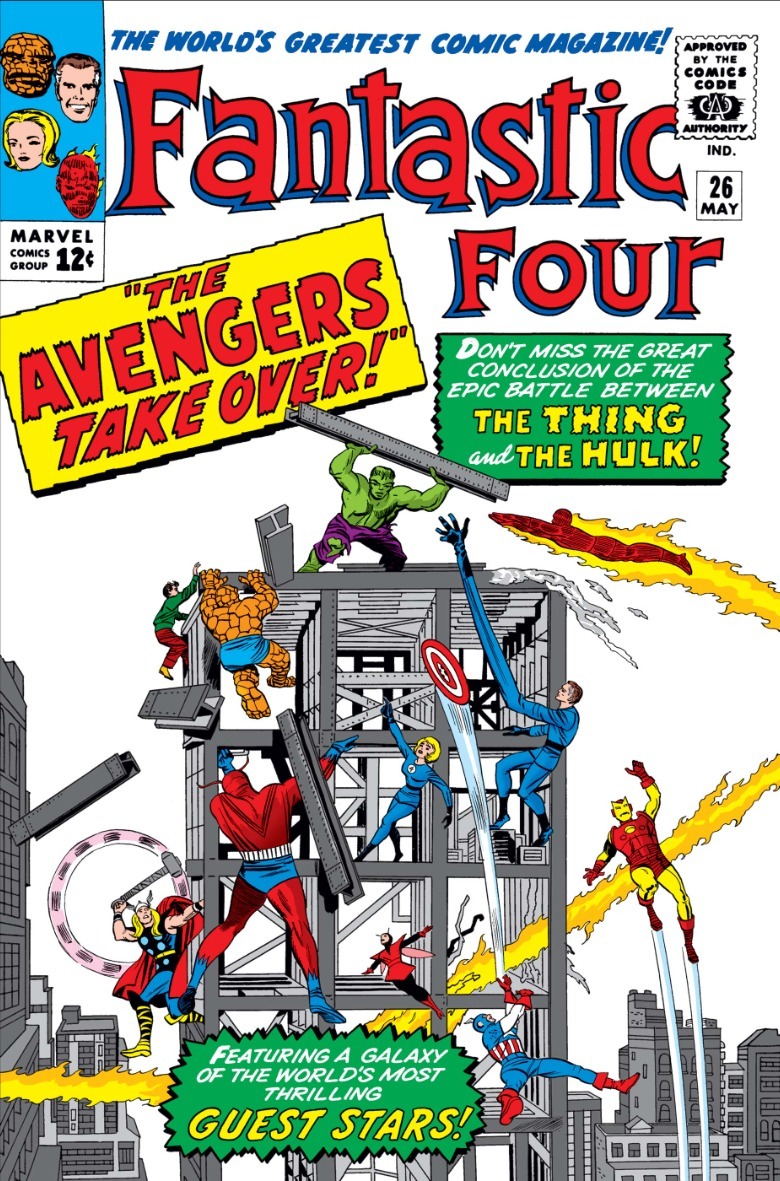

What most people know as Marvel Comics has used a shared universe since the beginning. All the major Marvel characters were created in the early '60s by artists like Jack Kirby and Steve Ditko, under the direction of editor Stan Lee. Like the MCU did during its early phases, the continuity whipped up a sense of awe for young readers, teaching them every issue was just a tapestry of a larger story.

The culmination of that, and the biggest crossover yet, was 1984-1985's "Secret Wars" (by Jim Shooter, Mike Zeck, and Bob Layton), where all the A-List Marvel heroes and villains are transported to "Battleworld" for a 12-issue epic smackdown. Every subsequent comic crossover has been chasing "Secret Wars" — it's to Marvel Comics what 2012's "The Avengers" was to the MCU.

Those Marvel crossovers long ago hit diminishing returns; there have been a couple of bright spots, like Chip Zdarsky's 2021 "Devil's Reign" or Kieron Gillen's 2022 "Judgement Day," but those are the exceptions. I promise as someone who does read comics, crossover "tie-in" issues that disrupt pacing are pure frustration.

The inescapable conclusion is that any series with this much story inevitably becomes inaccessible, which is a problem when you want a mass audience.

Is Marvel making the right call?

To get that audience, veteran comics writer Gerry Conway has proposed a wholesale (and unheeded so far) overhaul of how the comics industry should function:

"I'd cancel every existing superhero comic book, and publish a limited new line for a Middle-Grade readership, simplify characters and storylines, and eliminate every 'event' that requires more than passing familiarity with the basic simplified continuity. Ten-fifteen titles. For existing readers, I'd offer a separate, higher priced graphic novel line with whatever expanded adult storylines creators and readers want to explore. But this would be separate. Not monthly. Not the mainstream."

Marvel Studios putting up walls between its productions is probably a good move. So is Marvel's current game plan to release fewer movies and TV; making too much of something to meet a quota is an easy way to lose control of a narrative. The MCU is nowhere near as expansive as the comics are, so getting its house in order and cutting off the vestigial branches while it still can is the right call.

While they're at it, Marvel could afford to let the movies they do make be more individualistic and let directors put more personal stamps on them. "Multiverse of Madness" was at its best when director Sam Raimi got to flex his "Evil Dead" roots.

In any case, both Marvel Comics and Marvel Studios have learned the lesson that you can't assume every member of the audience is already your fan.